Solveig Jülich on Lennart Nilsson

Solveig Jülich is Professor of History of Science and Ideas at Uppsala University. For several years, she has been engaged in a research project that examines the historical conditions of Lennart Nilsson’s photographic work and its impact on the visual culture of pregnancy over time. She has written articles on the making of A Child Is Born in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine and the history of the various editions and translations of this best-selling pregnancy guide in Culture Unbound. Furthermore, she has published an essay in Social History of Medicine that shows how Nilsson’s early pictures of embryos and fetuses were featured in anti-abortion reports in the Swedish weekly press. Most recently, she has contributed a chapter on the connections between Nilsson’s photographs of human development and reproductive research in Sweden during the 1950s and 1960s in Rethinking the Public Fetus: Historical Perspectives on the Visual Culture of Pregnancy (University of Rochester Press, 2024). The broader theme of the historical links between medical research, abortion, and the uses of fetuses is developed in Histories of Fetal Knowledge Production in Sweden: Medicine, Politics, and Public Controversy, 1530–2020 (Brill, 2024).

-

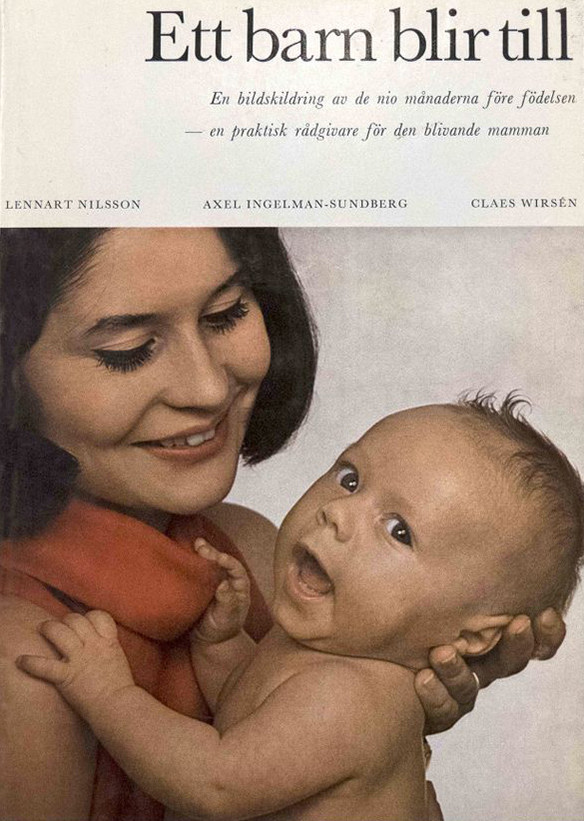

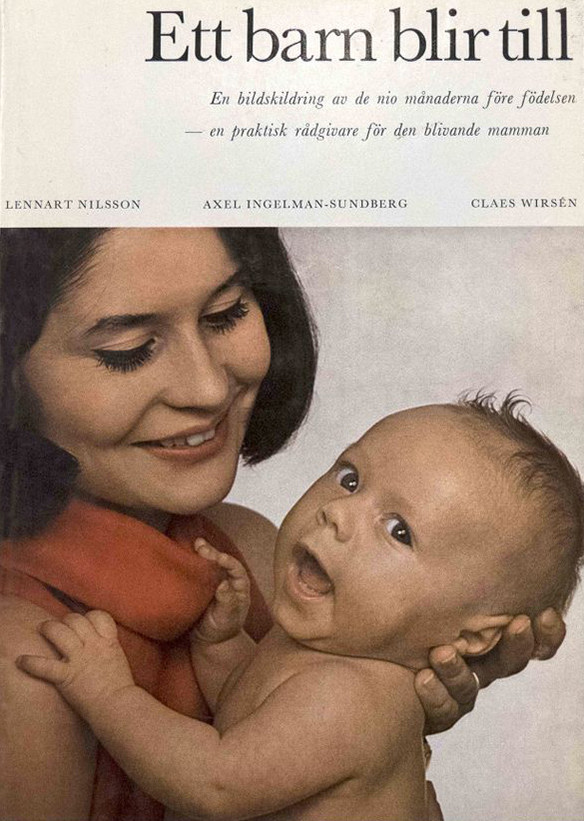

Ett barn blir till, 1:a editionen 1965 -

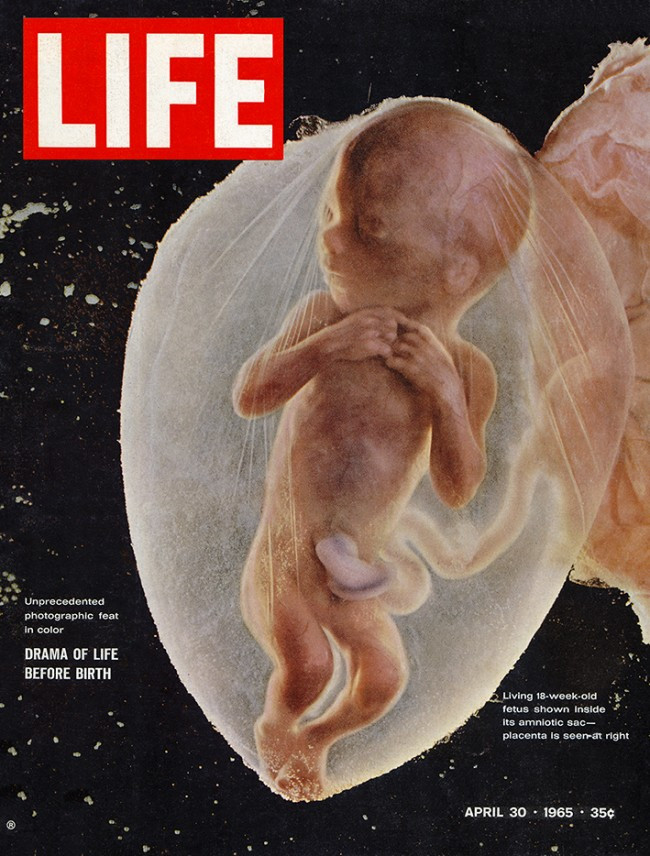

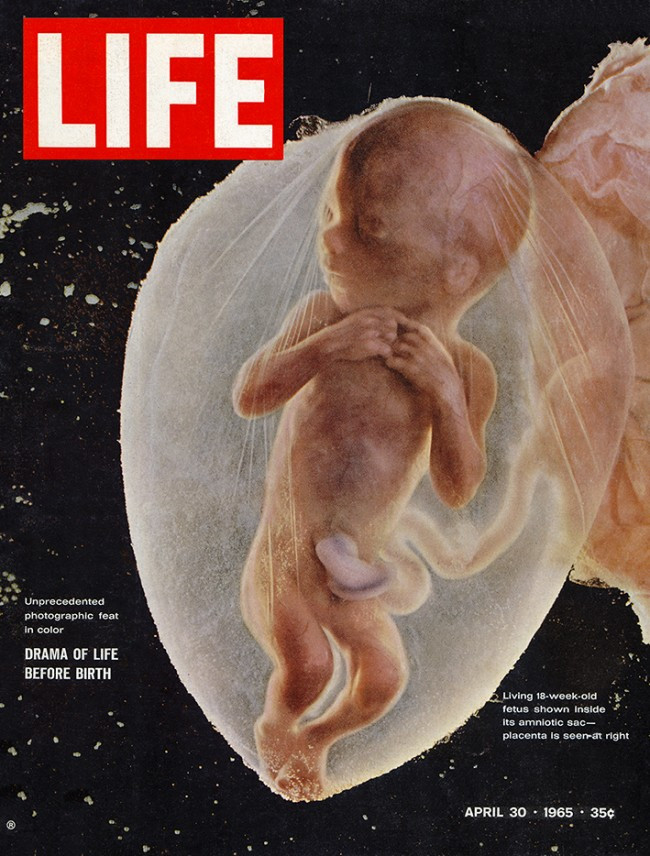

Life Magazine, 30 april 1965 -

Sexualundervisning av elever vid en skola i Stockholmsområdet 1967 ©Lennart Nilsson/TT

-

Ett barn blir till, 1:a editionen 1965 -

Life Magazine, 30 april 1965 -

Sexualundervisning av elever vid en skola i Stockholmsområdet 1967 ©Lennart Nilsson/TT

Jülich is currently finalizing a book manuscript, provisionally titled “Lennart Nilsson’s Icons of Life: Photography, Science, and the Image Economy, 1940–2010.” Building on previously unavailable material from his private archive, this book is the first to tell the extraordinary story of how Nilsson created the ground-breaking fetal pictures of the 1965 Life magazine issue and how he rose to international fame. From 1940 to the 1960s, Nilsson expanded reportage photography to include scientific and medical news. He also brought the visual style of medical reportage into new markets such as book publishing and film. From about 1970 to 2010, he had access to a laboratory at the prestigious Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, which awards the Nobel Prize. Along the way, he rebranded himself as a scientific and medical photographer. In recognition of his exceptional work in the service of knowledge, the Swedish government awarded him the honorary title of professor. For a generation that grew up with A Child Is Born, he came to be viewed by many as a kind of national icon, similar to Astrid Lindgren, Ingmar Bergman, and ABBA.

However, Nilsson could not have achieved these things on his own. A central argument is that he was part of an emerging network that included magazine editors, reporters, publishers, television producers, doctors, researchers, photographic experts, and technical assistants. Medical professionals provided him with human fetuses and body parts from abortions, surgeries, and autopsies. Through his photographic skills, the use of color film and colorization methods, he aestheticized the dead material and gave it the appearance of life. Combining photography and lenses with scientific and medical techniques such as light microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and endoscopy, he was able to achieve extreme angles and dramatic scenarios, always with his commercial interests in mind. Nilsson’s publishing house, photo agencies, picture magazines, Swedish National Television, and the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim circulated the photographs in the ever-growing image economy.

Examining Nilsson’s photographic activities over more than half a century sheds light on a larger narrative about Sweden, including its role in controversial human fetal research, national abortion conflicts, and the establishment of sex education in the progressive welfare state. Nilsson’s publications have made medical and biological knowledge widely available. However, they have also created ignorance about what people see in the pictures and how they were made.

This book bridges history of science, medical history, media studies, and history of photography. It offers new insights into how a certain kind of twentieth century images became powerful icons of life and knowledge by putting them back in the places where they were produced, circulated, and viewed.